放疗(RT)联合/不联合化疗、手术等其他治疗手段是头颈部肿瘤患者常见的治疗/姑息方法[1]。头颈部区域的放疗不可避免地会导致一系列口腔相关并发症,最常见的是黏膜炎、唾液腺损伤和龋齿等,表现为疼痛、口干、进食障碍、发音障碍、牙齿缺失等症状,严重影响了患者的治疗进程和生活质量。本文针对头颈部肿瘤尤其是鼻咽癌放疗导致的口腔并发症及其发病机制、防治进展进行重点阐述。

一、放射性口腔黏膜炎(radiation-induced oral mucositis, RIOM)1. 临床表现:头颈部放疗期间RIOM发病率高达80%;当总辐射剂量超过30 Gy时,罹患RIOM风险接近100%[2-3]。RIOM早期主要表现为局部黏膜红斑,继续进展可出现全口腔黏膜范围的深溃疡和假膜[4]。不同部位的口腔黏膜出现RIOM的严重程度不同,以软腭最为严重,其次是下咽黏膜、口底、颊、舌根、唇和舌背。患者出现疼痛、吞咽困难、语言障碍、进食障碍,常伴有营养恶化和感染风险,严重时需要人工喂养。

2. 病理机制:RIOM涉及的辐射敏感细胞包括上皮细胞、基底细胞、血管内皮细胞、成纤维细胞和先天免疫细胞等,其中以基底细胞为主要损伤靶点;其发生和发展主要为5个阶段:启动、主要损伤反应、信号放大、溃疡和愈合[3]。早期以细胞死亡和黏膜的完整性破坏来启动,后续激活免疫炎症反应进行效应放大[5-6]。大量炎症因子(包括IL-17等)释放会招募外周循环中的单核细胞和中性粒细胞,并增加血管内皮通透性,加重黏膜损伤。后续黏膜变脆变薄,最终形成溃疡、假膜,细菌定植风险也显著提高;同时神经末梢暴露,患者因此疼痛明显[3]。因此,RIOM的发生发展是一个上皮细胞、间质细胞、免疫细胞发生复杂的交互作用的病理过程。NF-κB被认为是RIOM中炎症调控最重要的转录因子,其活化可以促进促炎因子如IL-1β、IL-6和TNF-α的生成[7-8]。TLR9可以结合致病细菌,激活NF-κB。TLR2和TLR4不仅可以通过MyD88信号通路上调NF-κB,促进RIOM,另一方面又可以诱导ABCB1/MDR1 P-gp和保护性细胞因子生成,促进损伤黏膜的恢复[9]。另外,在放疗期间,患者感染机会致病菌和真菌概率也显著增加[10],梭菌属、卟啉单胞菌属、密螺旋体属和普氏菌属在细菌群落中的丰度变化呈显著同步,其峰值常与严重口腔黏膜炎(SOM)的发生相一致,表明口腔黏膜微生物群的失调可能会加剧RIOM,这一过程可能通过提高促炎因子的表达而实现[11-12]。

3. 治疗措施

(1) 非药物预防:保持良好的口腔卫生,避免进食刺激性如辛辣、过热、过酸的食物,戒烟戒酒;推荐每天用柔软的牙刷刷牙4~6次,使用不含乙醇的生理盐水或碱性(碳酸氢钠)漱口水清洁口腔;使用口腔保湿剂如干口含片等[1, 13]。

(2) 照射剂量:剂量限制,如佩戴定制支架向舌侧偏移、采取调强放疗、分割放疗等,有助于控制RIOM发生发展的第一阶段[14]。

(3) 抗炎药物:肿瘤支持治疗多国协会(MASCC) 建议接受≥50 Gy剂量放疗的头颈部肿瘤患者使用苯二胺漱口液,能降低红斑和溃疡发生率[15]。常用中药配方双花白鹤片(SBT)进行抗炎处理,可以有效降低促炎因子如IL-17和TNF-α的产生以及Treg细胞的浸润[16]。戊酮可可碱是一种非特异性磷酸二酯酶抑制剂,可阻断TGF-β1的转录;维生素E对TGF-β的产生亦具有抑制作用[17]。

(4) 信号调控:氯化锂(LiCl)是Wnt/β-连环蛋白信号通路的有效激活剂,可促进上皮基底层细胞增殖和味蕾细胞的更新,起到恢复口腔黏膜完整性和味觉功能的作用[18]。沙利度胺可以通过miR-9-3p/NFATC2/NF-NF-kB轴减弱放疗诱导的口腔上皮细胞凋亡和促炎因子分泌[19]。BMI-1通过抑制p16Ink4a、p19Arf和p21转录来维持干细胞的自我更新和增殖能力,在RIOM中其表达受到抑制。利用槲皮素预处理增强BMI-1的表达,可以抑制ROS的释放,下调NF-κB信号通路,促进DNA损伤修复和干细胞增殖,从而促进黏膜愈合[20]。

(5) 抗氧化药物:临床试验表明,谷氨酰胺对接受放疗的头颈部肿瘤患者可以显著降低≥3级RIOM的严重程度和持续时间,可能与其代谢副产物谷胱甘肽防止氧化应激、对抗促炎介质的产生有关[21]。Anderson等[22]进行的ⅡB期研究表明,阿瓦索帕森锰(Avasopasem Mn,GC4419)可以将RIOM的病程从19 d缩短至1.5 d,SOM的发病率也从65%降至43%。起到类似抗氧化效果的药物还有蜂胶和锌。蜂胶中含有大量带有羟基的芳香环,锌可以诱导金属硫蛋白的合成,都能有效减少自由基和活性氧的生成[23-25]。另外,Nrf2在消除ROS和减少DNA损伤方面有重要作用,Nrf2激活的小鼠辐射损受损后比Nrf2敲除的小鼠舌黏膜角质层增厚,抑制了黏膜炎的进展,提示针对Nrf2靶点在黏膜炎的预防和治疗方面具有一定前景[26]。

(6) 生长因子:生长因子可以有效促进上皮细胞生长和角化,从而缓解RIOM。候选因子主要包括粒细胞-巨噬细胞集落刺激因子(GM-CSF)和粒细胞集落刺激因子(G-CSF)、重组牛碱性成纤维细胞生长因子(rb-bFGF)和重组人表皮生长因子(rhEGF)等,均可推迟RIOM的发生,降低Ⅲ、Ⅳ级黏膜炎的发生率[27]。

(7) 其他治疗:短期局部使用糖皮质激素能减轻水肿,抑制炎症反应,缓解患者的症状;但长期使用会增加真菌感染、免疫抑制的风险[28]。此外,高压氧治疗(HBO)不仅可以促进成纤维细胞凋亡、抑制成纤维细胞活化,促进血管内皮生长因子的表达,还能抑制TNF-α和TGF-β分泌,提示其在RIOM的治疗方面亦具有一定前景[29]。

二、放射性唾液腺损伤(radiation-induced salivary gland injury, RISGI)1. 临床表现:研究表明,在鼻咽癌常规头颈野放疗后RISGI的发生率近乎100%[30]。RISGI主要表现在唾液流量减少和唾液成分改变。唾液流量减低在放疗开始到治疗结束3个月后最显著,尤其是在治疗开始的第一周,可达50%~60%,随之患者出现明显的口干症状[31]。唾液成分改变包括碳酸氢盐等缓冲离子的浓度降低、酶和免疫蛋白缺乏等,导致唾液pH值下降、变得高度黏稠,缓冲能力和免疫功能降低,随之出现黏膜炎、放射性龋齿(RIC)、继发感染等症状[32-33];严重RISGI患者的口干症状会持续数年至数十年,甚至伴随终生[34]。

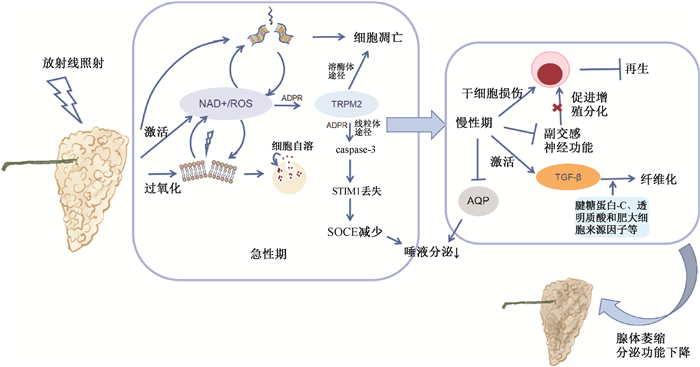

2. 病理机制:急性期以上皮细胞凋亡和脂质过氧化为主。放射线导致DNA损伤,同时显著增加自由基和活性氧(ROS)的水平,诱导氧化应激,导致腺泡细胞和微血管内皮细胞凋亡[35-36];腺泡细胞的分泌颗粒膜过氧化,破裂释放酶,导致细胞自溶[35]。唾液分泌依赖于钙池调控钙内流通道(store-operated Ca2+ entry,SOCE),见图 1。研究表明,放射线损伤导致大量NAD+和ROS产生,通过动员二磷酸腺苷核糖(ADPR)并与其协同作用,激活瞬时受体电位M2型(TRPM2)依赖性线粒体途径,导致SOCE减少,进而减少唾液分泌。除了抑制唾液分泌,TRPM2还可以作为溶酶体Ca2+释放通道,介导腺泡细胞凋亡[37-40]。

|

注:NAD. 尼克酰胺腺嘌呤二核苷酸;ADPR. 二磷酸腺苷核糖;SOCE. 钙池调控钙内流通道;STIMI. SOCE的Ca2+传感器蛋白;TRPM2. 瞬时受体电位M2型离子通道;AQP. 水通道蛋白 图 1 放射性唾液腺损伤的发病机制 Figure 1 Pathogenesis of radiation-induced salivary gland injury |

慢性期以唾液腺干细胞再生障碍和间质纤维化为主。再生障碍的机制复杂,其中副交感神经分泌的Ach可以促进干细胞的增殖和分化;而放疗减少脑源性神经营养因子(BDNF)、神经营养因子和神经生长因子的表达,直接导致副交感神经功能的下调[41-43]。在组织修复后期,TGF-β信号通路的激活以及在腱糖蛋白-C、透明质酸和肥大细胞来源因子等参与下腺体纤维化,导致腺体分泌功能丧失[44-45]。此外,AQP1和AQP5是唾液分泌的重要通道蛋白;TGF-β超家族成员骨形态发生蛋白6(BMP6)上调可导致AQP5下调和唾液分泌减少[46],相关机制有待于在放射损伤模型中进一步明确。

3. 治疗措施

(1) 非药物措施:主要包括保持口腔卫生、刺激唾液分泌、规划辐射范围等[47]。

(2) 抗氧化剂:Ren等[48]自主合成了一种活性氧清除剂HL-003,可以保护唾液上皮细胞膜上的AQP-5蛋白免受辐射损伤,同时抑制氧化应激和p53的激活,从而减少细胞凋亡。槲皮素和纳林宁也可以起到抗氧化,保护下颌下腺的作用[49]。

(3) 信号调控分子:Sialin (SLC17A5)是人细胞膜硝酸盐转运通道,在唾液腺上表达水平最高。口服硝酸盐后,Sialin表达水平显著提高,与硝酸盐组成“硝酸盐-Sialin反馈环路”(nitrate-sialin feedback loop),激活EGFR-AKT-MAPK信号通路,从而减少辐射诱导的唾液腺腺泡细胞凋亡,促进增殖[50]。目前,该项研究已经研发了基于无机硝酸盐新药——耐瑞特尔并申请专利,正在积极推进临床研究。

(4) 生长因子:肝细胞生长因子(hepatocyte growth factors)可以通过HGF-MET-PI3K-AKT轴抑制腺泡细胞凋亡,保护唾液腺[51]。

(5) 干细胞:研究显示,将唾液腺干细胞移植到辐照损伤的唾液腺组织中,干细胞能在导管处定植并完成增殖分化,形成腺泡和导管样结构;其中以c-kit+的干细胞具有明显优势[52-54]。将同种异体脂肪组织衍生的间充质干/基质细胞(AT-MSCs)注入口干症患者的下颌下腺和腮腺,没有观察到严重不良反应且唾液流速增加,口腔干燥症缓解[54]。然而,干细胞治疗还面临着干细胞获取数量不足、可能存在免疫排斥反应、瘤变等问题。因此,干细胞的研究目前逐渐向内源性干细胞的激活转变:利用干细胞分泌的生物活性因子来激活内源性唾液腺干细胞,从而修复放射性损伤的唾液腺组织[55]。

三、放射性龋齿(radiation-induced caries, RIC)1. 临床表现:RIC通常在放疗结束后6~12个月出现,进展迅速,严重的情况下原本健康的牙列可能在1年内完全丧失。龋齿向深处进展可能导致根尖周炎,进而出现放射性骨坏死风险的提高[56-57]。与一般的龋齿不同,放射性龋齿主要出现在牙颈部(尤其靠近釉牙骨质界的位置)、切缘和牙尖,尤其是下颌前牙的舌面[58-59]。早期表现为牙齿黑色/棕色变色以及牙釉质裂纹;继而进展为牙釉质脱落、牙本质暴露,牙冠的支持力不足,最终导致牙齿折裂甚至仅余残根[58, 60]。

2. 病理机制:目前主要认为是唾液腺的损伤以及其导致的一系列口腔症状决定了RIC发生发展[57]。唾液pH值降至5.3时RIC的风险增加,而研究表明放疗后唾液平均pH可从6.259降至4.580[61]。同时,唾液流量减少、稠度增加降低了对菌斑的清除率和缓冲能力;牙齿表面细菌生物膜沉积,利于产酸致龋菌如乳杆菌、变异链球菌等微生物生长[62],导致口腔微生态环境失衡。此外,放疗后患者味觉丧失,甜味和咸味的丧失最晚出现;为了维持营养,患者也通常进食富含碳水化合物的高致龋性食物[63-64]。这些都会打破牙体硬组织脱矿和再矿化的平衡,导致牙釉质和牙本质的破坏[58]。

除了间接损伤,辐射也可能会对牙体的无机和有机成分造成直接破坏。研究发现,经过辐射暴露后,釉牙本质界(dentinoenamel junction, DEJ)附近牙釉质的矿化程度、显微硬度和弹性模量降低[65-66];同时,DEJ处基质金属蛋白酶-20的过表达也会增加DEJ的不稳定性,牙釉质容易出现裂纹、脱落[67-68]。牙本质显微硬度的降低、胶原纤维断裂也会促进裂纹形成、干扰修复[66]。但也有研究出现与上述情况相悖的结论[69-71]。因此,辐射对牙体组织的直接损伤机制还有待更深入的研究。

3. 防治措施:对于RIC的预防,最理想的情况是应在肿瘤确诊即开始[72]。基于人工智能神经网络,从全景照片中提取特征来预测和检测RIC,其精度可达99.2%,展现出良好的应用前景[73]。保持口腔卫生清洁,刺激唾液分泌,缓解口干症状,利用氟化物防龋,以及对已有缺损的牙和牙列进行永久性修复,是RIC的预防和治疗的主要手段。可以每天使用0.12%氯己定漱口液和1%中性氟化钠凝胶防龋、促进再矿化[74-75]。目前临床上也采用含氟材料如树脂改性含钙玻璃离子水门汀(RMGIC)以及氟化二胺银(SDF)进行专业防龋操作[76-77]。对于需进行永久性修复的患者,目前对于修复材料和方法的选择仍没有参考标准,通常基于医师的临床经验而定;加之RIC患者特殊的口腔环境,永久性修复的成功率不高[72, 78],未来还需要完善治疗方案和提高修复材料的性能。

四、小结与展望头颈部肿瘤放疗引起口腔并发症,会不同程度地影响患者的生活质量、治疗进展和长期生存。本文系统地总结了头颈部肿瘤放疗后口腔相关并发症的临床表现、病理机制和治疗措施的研究进展。RIOM、RISGI和RIC并非相互独立:RISGI导致的唾液分泌减低是RIC主要的致病因素,其继发的口腔环境的改变与RIOM的发生发展密切相关;而RIOM造成的疼痛、感染、进食障碍,同样也会加重RISGI和RIC的病情。但目前对于相关病理机制和干预研究大多处于动物实验阶段,尚待进一步明确其临床意义。例如,利用生长因子可缓解RIOM症状,促进黏膜再生,但无针对性使用生长因子可能导致残余肿瘤细胞生长和复发,因此其在实际临床使用中存在一些顾虑。对于罹患RIC仅余残根的患者,因其牙体结构遭到破坏,临床对于此类残根修复相当困难;但经典理论认为放疗后5年内不宜拔牙,导致进一步治疗无法进行,进而引起患者生活质量无法改善。未来,针对这些问题的进一步解析,并结合组学技术,干细胞培养和移植、材料学等领域的进展,预见会有越来越多贴近临床的治疗新措施涌现。

利益冲突 无

作者贡献声明 王植、潘莹紫负责文献调研和论文撰写;陈铭晟、王锋超指导论文框架、文献调研、论文撰写和修改

| [1] |

Buglione M, Cavagnini R, Di Rosario F, et al. Oral toxicity management in head and neck cancer patients treated with chemotherapy and radiation: Dental pathologies and osteoradionecrosis (Part 1) literature review and consensus statement[J]. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 2016, 97: 131-142. DOI:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.08.010 |

| [2] |

Luitel A, Rimal J, Maharjan IK, et al. Assessment of oral mucositis among patients undergoing radiotherapy for head and neck cancer: An audit[J]. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ), 2019, 17(65): 61-65. |

| [3] |

Sonis ST. The pathobiology of mucositis[J]. Nat Rev Cancer, 2004, 4(4): 277-284. DOI:10.1038/nrc1318 |

| [4] |

Sonis ST. Oral mucositis[J]. Anticancer Drugs, 2011, 22(7): 607-612. DOI:10.1097/CAD.0b013e3283462086 |

| [5] |

Liu S, Zhao Q, Zheng Z, et al. Status of treatment and prophylaxis for radiation-induced oral mucositis in patients with head and neck cancer[J]. Front Oncol, 2021, 11: 642575. DOI:10.3389/fonc.2021.642575 |

| [6] |

Lee CT, Galloway TJ. Pathogenesis and amelioration of radiation-induced oral mucositis[J]. Curr Treat Options Oncol, 2022, 23(3): 311-324. DOI:10.1007/s11864-022-00959-z |

| [7] |

Sonis ST. The biologic role for nuclear factor-kB in disease and its potential involvement in mucosal injury associated with anti-neoplastic therapy[J]. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med, 2002, 13(5): 380-389. DOI:10.1177/154411130201300502 |

| [8] |

Criswell T, Leskov K, Miyamoto S, et al. Transcription factors activated in mammalian cells after clinically relevant doses of ionizing radiation[J]. Oncogene, 2003, 22(37): 5813-5827. DOI:10.1038/sj.onc.1206680 |

| [9] |

Ji L, Hao S, Wang J, et al. Roles of Toll-like receptors in radiotherapy- and chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis: A concise review[J]. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2022, 12: 831387. DOI:10.3389/fcimb.2022.831387 |

| [10] |

Ingrosso G, Saldi S, Marani S, et al. Breakdown of symbiosis in radiation-induced oral mucositis[J]. J Fungi (Basel), 2021, 7(4): 290. DOI:10.3390/jof7040290 |

| [11] |

Hou J, Zheng H, Li P, et al. Distinct shifts in the oral microbiota are associated with the progression and aggravation of mucositis during radiotherapy[J]. Radiother Oncol, 2018, 129(1): 44-51. DOI:10.1016/j.radonc.2018.04.023 |

| [12] |

Gugnacki P, Sierko E. Is there an interplay between oral microbiome, head and neck carcinoma and radiation-induced oral mucositis?[J]. Cancers (Basel), 2021, 13(23): 5902. DOI:10.3390/cancers13235902 |

| [13] |

中华医学会放射肿瘤治疗学分会. 放射性口腔黏膜炎防治策略专家共识(2019)[J]. 中华放射肿瘤学杂志, 2019, 28(9): 641-647. Chinese Society of Radiation Oncology, Chinese Medical Association. Expert consensus on prevention and control strategy of radiotherapy-induced oral mucositis (2019)[J]. Chin J Radiat Oncol, 2019, 28(9): 641-647. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.1004-4221.2019.09.001 |

| [14] |

Grant SR, Williamson TD, Stieb S, et al. A dosimetric comparison of oral cavity sparing in the unilateral treatment of early stage tonsil cancer: IMRT, IMPT, and tongue-deviating oral stents[J]. Adv Radiat Oncol, 2020, 5(6): 1359-1363. DOI:10.1016/j.adro.2020.08.007 |

| [15] |

Epstein JB, Silverman S Jr, Paggiarino DA, et al. Benzydamine HCl for prophylaxis of radiation-induced oral mucositis: results from a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial[J]. Cancer, 2001, 92(4): 875-885. DOI:10.1002/1097-0142(20010815)92:4<875::aid-cncr1396>3.0.co;2-1 |

| [16] |

Geng QS, Liu RJ, Shen ZB, et al. Transcriptome sequencing and metabolome analysis reveal the mechanism of Shuanghua Baihe Tablet in the treatment of oral mucositis[J]. Chin J Nat Med, 2021, 19(12): 930-943. DOI:10.1016/S1875-5364(22)60150-X |

| [17] |

Sayed R, El Wakeel L, Saad AS, et al. Pentoxifylline and vitamin E reduce the severity of radiotherapy-induced oral mucositis and dysphagia in head and neck cancer patients: a randomized, controlled study[J]. Med Oncol, 2019, 37(1): 8. DOI:10.1007/s12032-019-1334-5 |

| [18] |

Zhu J, Zhang H, Li J, et al. LiCl promotes recovery of radiation-induced oral mucositis and dysgeusia[J]. J Dent Res, 2021, 100(7): 754-763. DOI:10.1177/0022034521994756 |

| [19] |

Liang L, Chen L, Liu G, et al. Thalidomide attenuates oral epithelial cell apoptosis and pro-inflammatory cytokines secretion induced by radiotherapy via the miR-9-3p/NFATC2/NF-κB axis[J]. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2022, 603: 102-108. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2022.03.030 |

| [20] |

Zhang J, Hong Y, Liuyang Z, et al. Quercetin prevents radiation-induced oral mucositis by upregulating BMI-1[J]. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2021, 2021: 2231680. DOI:10.1155/2021/2231680 |

| [21] |

Alsubaie HM, Alsini AY, Alsubaie KM, et al. Glutamine for prevention and alleviation of radiation-induced oral mucositis in patients with head and neck squamous cell cancer: Systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials[J]. Head Neck, 2021, 43(10): 3199-3213. DOI:10.1002/hed.26798 |

| [22] |

Anderson CM, Lee CM, Saunders DP, et al. Phase Ⅱb, randomized, double-blind trial of GC4419 versus placebo to reduce severe oral mucositis due to concurrent radiotherapy and cisplatin for head and neck cancer[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2019, 37(34): 3256-3265. DOI:10.1200/JCO.19.01507 |

| [23] |

Al-Hatamleh M, Boer JC, Wilson KL, et al. Antioxidant-based medicinal properties of stingless bee products: Recent progress and future directions[J]. Biomolecules, 2020, 10(6): 923. DOI:10.3390/biom10060923 |

| [24] |

Hamzah MH, Mohamad I, Musa MY, et al. Propolis mouthwash for preventing radiotherapy-induced mucositis in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma[J]. Med J Malaysia, 2022, 77(4): 462-467. |

| [25] |

Lin LC, Que J, Lin LK, et al. Zinc supplementation to improve mucositis and dermatitis in patients after radiotherapy for head-and-neck cancers: a double-blind, randomized study[J]. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys, 2006, 65(3): 745-750. DOI:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.01.015 |

| [26] |

Wakamori S, Taguchi K, Nakayama Y, et al. Nrf2 protects against radiation-induced oral mucositis via antioxidation and keratin layer thickening[J]. Free Radic Biol Med, 2022, 188: 206-220. DOI:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2022.06.239 |

| [27] |

李素艳, 高黎, 殷蔚伯, 等. 金因肽对急性放射性黏膜炎及皮炎的作用[J]. 中华放射肿瘤学杂志, 2002, 11(1): 30-32. Li SY, Gao L, Yin WB, et al. Effect of Gene Time on acute radiation mucositis and dermatitis[J]. Chin J Radiat Oncol, 2002, 11(1): 30-32. DOI:10.3760/j.issn:1004-4221.2002.01.009 |

| [28] |

Nishii M, Soutome S, Kawakita A, et al. Factors associated with severe oral mucositis and candidiasis in patients undergoing radiotherapy for oral and oropharyngeal carcinomas: a retrospective multicenter study of 326 patients[J]. Support Care Cancer, 2020, 28(3): 1069-1075. DOI:10.1007/s00520-019-04885-z |

| [29] |

闫越琪. 高压氧治疗口腔潜在恶性病变的研究现况[J]. 临床口腔医学杂志, 2018, 34(9): 566-569. Yan YQ. Study status on hyperbaric oxygen therapy for oral potential malignancy[J]. Clin Stomatol Med J, 2018, 34(9): 566-569. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1003-1634.2018.09.017 |

| [30] |

Redman RS. On approaches to the functional restoration of salivary glands damaged by radiation therapy for head and neck cancer, with a review of related aspects of salivary gland morphology and development[J]. Biotech Histochem, 2008, 83(3-4): 103-130. DOI:10.1080/10520290802374683 |

| [31] |

Franzén L, Funegård U, Ericson T, et al. Parotid gland function during and following radiotherapy of malignancies in the head and neck. A consecutive study of salivary flow and patient discomfort[J]. Eur J Cancer, 1992, 28(2-3): 457-462. DOI:10.1016/s0959-8049(05)80076-0 |

| [32] |

Sciubba JJ, Goldenberg D. Oral complications of radiotherapy[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2006, 7(2): 175-183. DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70580-0 |

| [33] |

Pinna R, Campus G, Cumbo E, et al. Xerostomia induced by radiotherapy: an overview of the physiopathology, clinical evidence, and management of the oral damage[J]. Ther Clin Risk Manag, 2015, 11: 171-188. DOI:10.2147/TCRM.S70652 |

| [34] |

赵云艳. 放射性唾液腺损伤机理的研究进展[J]. 临床肿瘤学杂志, 2010, 15(6): 572-574. Zhao YY. Mechanisms of radiation-induced salivary glands dysfunction[J]. Chin Clin Oncol, 2010, 15(6): 572-574. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1009-0460.2010.06.024 |

| [35] |

李审绥, 吴沉洲, 乔翔鹤, 等. 辐射损伤唾液腺机制及治疗的研究进展[J]. 华西口腔医学杂志, 2021, 39(1): 99-104. Li SS, Wu CZ, Qiao XH, et al. Advances on mechanism and treatment of salivary gland in radiation injury[J]. West China J Stomatol, 2021, 39(1): 99-104. DOI:10.7518/hxkq.2021.01.015 |

| [36] |

Liu Z, Dong L, Zheng Z, et al. Mechanism, prevention, and treatment of radiation-induced salivary gland injury related to oxidative stress[J]. Antioxidants (Basel), 2021, 10(11): 1666. DOI:10.3390/antiox10111666 |

| [37] |

Ogawa N, Kurokawa T, Mori Y. Sensing of redox status by TRP channels[J]. Cell Calcium, 2016, 60(2): 115-122. DOI:10.1016/j.ceca.2016.02.009 |

| [38] |

Sumoza-Toledo A, Penner R. TRPM2: a multifunctional ion channel for calcium signalling[J]. J Physiol, 2011, 589(Pt 7): 1515-1525. DOI:10.1113/jphysiol.2010.201855 |

| [39] |

Liu X, Cotrim A, Teos L, et al. Loss of TRPM2 function protects against irradiation-induced salivary gland dysfunction[J]. Nat Commun, 2013, 4: 1515. DOI:10.1038/ncomms2526 |

| [40] |

Liu X, Gong B, de Souza LB, et al. Radiation inhibits salivary gland function by promoting STIM1 cleavage by caspase-3 and loss of SOCE through a TRPM2-dependent pathway[J]. Sci Signal, 2017, 10(482): 4064. DOI:10.1126/scisignal.aal4064 |

| [41] |

Emmerson E, May AJ, Berthoin L, et al. Salivary glands regenerate after radiation injury through SOX2-mediated secretory cell replacement[J]. EMBO Mol Med, 2018, 10(3): e8051. DOI:10.15252/emmm.201708051 |

| [42] |

Tanida S, Kataoka H, Mizoshita T, et al. Intranuclear translocation signaling of HB-EGF carboxy-terminal fragment and mucosal defense through cell proliferation and migration in digestive tracts[J]. Digestion, 2010, 82(3): 145-149. DOI:10.1159/000310903 |

| [43] |

Knox SM, Lombaert IM, Reed X, et al. Parasympathetic innervation maintains epithelial progenitor cells during salivary organogenesis[J]. Science, 2010, 329(5999): 1645-1647. DOI:10.1126/science.1192046 |

| [44] |

Bartel-Friedrich S, Lautenschläger C, Holzhausen HJ, et al. Expression and distribution of tenascin in rat submandibular glands following irradiation[J]. Anticancer Res, 2010, 30(5): 1593-1598. |

| [45] |

Henriksson R, Fröjd O, Gustafsson H, et al. Increase in mast cells and hyaluronic acid correlates to radiation-induced damage and loss of serous acinar cells in salivary glands: the parotid and submandibular glands differ in radiation sensitivity[J]. Br J Cancer, 1994, 69(2): 320-326. DOI:10.1038/bjc.1994.58 |

| [46] |

Lai Z, Yin H, Cabrera-Pérez J, et al. Aquaporin gene therapy corrects Sjögren's syndrome phenotype in mice[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2016, 113(20): 5694-5699. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1601992113 |

| [47] |

Buglione M, Cavagnini R, Di Rosario F, et al. Oral toxicity management in head and neck cancer patients treated with chemotherapy and radiation: Xerostomia and trismus (Part 2). Literature review and consensus statement[J]. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 2016, 102: 47-54. DOI:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.03.012 |

| [48] |

Ren J, Huang R, Li Y, et al. Radioprotective effects and mechanism of HL-003 on radiation-induced salivary gland damage in mice[J]. Sci Rep, 2022, 12(1): 8419. DOI:10.1038/s41598-022-12581-y |

| [49] |

Sakat MS, Kılıç K, Sahin A, et al. The protective efficacy of Quercetin and Naringenin against radiation-related submandibular gland injury in female rats: A histopathological, immunohistochemical, and biochemical study[J]. Arch Oral Biol, 2022, 142: 105510. DOI:10.1016/j.archoralbio.2022.105510 |

| [50] |

Feng X, Wu Z, Xu J, et al. Dietary nitrate supplementation prevents radiotherapy-induced xerostomia[J]. Elife, 2021, 10: e70710. DOI:10.7554/eLife.70710 |

| [51] |

Yoon YJ, Shin HS, Lim JY. A hepatocyte growth factor/MET-induced antiapoptotic pathway protects against radiation-induced salivary gland dysfunction[J]. Radiother Oncol, 2019, 138: 9-16. DOI:10.1016/j.radonc.2019.05.012 |

| [52] |

Lombaert I, Movahednia MM, Adine C, et al. Concise review: Salivary gland regeneration: Therapeutic approaches from stem cells to tissue organoids[J]. Stem Cells, 2017, 35(1): 97-105. DOI:10.1002/stem.2455 |

| [53] |

Pringle S, Maimets M, van der Zwaag M, et al. Human salivary gland stem cells functionally restore radiation damaged salivary glands[J]. Stem Cells, 2016, 34(3): 640-652. DOI:10.1002/stem.2278 |

| [54] |

Lynggaard CD, Grønhøj C, Christensen R, et al. Intraglandular off-the-shelf allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell treatment in patients with radiation-induced xerostomia: A safety study (MESRIX-Ⅱ)[J]. Stem Cells Transl Med, 2022, 11(5): 478-489. DOI:10.1093/stcltm/szac011 |

| [55] |

黄桂林. 放射性唾液腺功能损伤的再生医学研究——从干细胞到无细胞治疗[J]. 口腔颌面外科杂志, 2022, 32(2): 71-76. Huang GL. Regenerative medicine research on radiation-induced salivary gland dysfunction: From stem cell therapy to cell-free therapy[J]. J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 2022, 32(2): 71-76. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1005-4979.2022.02.001 |

| [56] |

余意, 陈冬平, 邝燕好, 等. 鼻咽癌放射性龋齿发病规律及相关因素分析[J]. 中华肿瘤防治杂志, 2017, 24(6): 379-382. Yu Y, Chen DP, Kuang YH, et al. Occurrence dynamics and analysis of influencing factors of radiation caries for the patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma[J]. Chin J Cancer Prev Treat, 2017, 24(6): 379-382. |

| [57] |

Chopra A, Monga N, Sharma S, et al. Indices for the assessment of radiation-related caries[J]. J Conserv Dent, 2022, 25(5): 481-486. DOI:10.4103/jcd.jcd_237_22 |

| [58] |

Kielbassa AM, Hinkelbein W, Hellwig E, et al. Radiation-related damage to dentition[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2006, 7(4): 326-335. DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70658-1 |

| [59] |

Madrid CC, de Pauli Paglioni M, Line SR, et al. Structural analysis of enamel in teeth from head-and-neck cancer patients who underwent radiotherapy[J]. Caries Res, 2017, 51(2): 119-128. DOI:10.1159/000452866 |

| [60] |

Palmier NR, Madrid CC, Paglioni MP, et al. Cracked tooth syndrome in irradiated patients with head and neck cancer[J]. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol, 2018, 126(4): 335-341. DOI:10.1016/j.oooo.2018.06.005 |

| [61] |

Petru BB, Elisabeta CL, Liliana FG, et al. The quantification of salivary flow and pH and stomatognathic system rehabilitation interference in patients with oral diseases, post-radiotherapy[J]. Appl Sci, 2022, 12(8): 3708. DOI:10.3390/app12083708 |

| [62] |

Epstein JB, Chin EA, Jacobson JJ, et al. The relationships among fluoride, cariogenic oral flora, and salivary flow rate during radiation therapy[J]. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod, 1998, 86(3): 286-292. DOI:10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90173-1 |

| [63] |

Hong CH, Napeñas JJ, Hodgson BD, et al. A systematic review of dental disease in patients undergoing cancer therapy[J]. Support Care Cancer, 2010, 18(8): 1007-1021. DOI:10.1007/s00520-010-0873-2 |

| [64] |

Brennan MT, Treister NS, Sollecito TP, et al. Dental disease before radiotherapy in patients with head and neck cancer: clinical registry of dental outcomes in head and neck cancer patients[J]. J Am Dent Assoc, 2017, 148(12): 868-877. DOI:10.1016/j.adaj.2017.09.011 |

| [65] |

Lu H, Zhao Q, Guo J, et al. Direct radiation-induced effects on dental hard tissue[J]. Radiat Oncol, 2019, 14(1): 5. DOI:10.1186/s13014-019-1208-1 |

| [66] |

Gonçalves LM, Palma-Dibb RG, Paula-Silva FW, et al. Radiation therapy alters microhardness and microstructure of enamel and dentin of permanent human teeth[J]. J Dent, 2014, 42(8): 986-992. DOI:10.1016/j.jdent.2014.05.011 |

| [67] |

Fonseca JM, Troconis CC, Palmier NR, et al. The impact of head and neck radiotherapy on the dentine-enamel junction: a systematic review[J]. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal, 2020, 25(1): e96-e105. DOI:10.4317/medoral.23212 |

| [68] |

Reed R, Xu C, Liu Y, et al. Radiotherapy effect on nano-mechanical properties and chemical composition of enamel and dentine[J]. Arch Oral Biol, 2015, 60(5): 690-697. DOI:10.1016/j.archoralbio.2015.02.020 |

| [69] |

Faria KM, Brandão TB, Ribeiro AC, et al. Micromorphology of the dental pulp is highly preserved in cancer patients who underwent head and neck radiotherapy[J]. J Endod, 2014, 40(10): 1553-1559. DOI:10.1016/j.joen.2014.07.006 |

| [70] |

Gomes-Silva W, Prado Ribeiro AC, de Castro Junior G, et al. Head and neck radiotherapy does not increase gelatinase (metalloproteinase-2 and -9) expression or activity in teeth irradiated in vivo[J]. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol, 2017, 124(2): 175-182. DOI:10.1016/j.oooo.2017.04.009 |

| [71] |

Gomes-Silva W, Prado-Ribeiro AC, Brandão TB, et al. Postradiation matrix metalloproteinase-20 expression and its impact on dental micromorphology and radiation-related caries[J]. Caries Res, 2017, 51(3): 216-224. DOI:10.1159/000457806 |

| [72] |

Palmier NR, Migliorati CA, Prado-Ribeiro AC, et al. Radiation-related caries: current diagnostic, prognostic, and management paradigms[J]. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol, 2020, 130(1): 52-62. DOI:10.1016/j.oooo.2020.04.003 |

| [73] |

De Araujo Faria V, Azimbagirad M, Viani Arruda G, et al. Prediction of radiation-related dental caries through PyRadiomics features and artificial neural network on panoramic radiography[J]. J Digit Imaging, 2021, 34(5): 1237-1248. DOI:10.1007/s10278-021-00487-6 |

| [74] |

Sroussi HY, Jessri M, Epstein J. Oral assessment and management of the patient with head and neck cancer[J]. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am, 2018, 30(4): 445-458. DOI:10.1016/j.coms.2018.06.006 |

| [75] |

Lopes C, Soares CJ, Lara VC, et al. Effect of fluoride application during radiotherapy on enamel demineralization[J]. J Appl Oral Sci, 2018, 27: e20180044. DOI:10.1590/1678-7757-2018-0044 |

| [76] |

Yu OY, Mei ML, Zhao IS, et al. Remineralisation of enamel with silver diamine fluoride and sodium fluoride[J]. Dent Mater, 2018, 34(12): e344-e352. DOI:10.1016/j.dental.2018.10.007 |

| [77] |

Scotti CK, Velo M, Brondino N, et al. Effect of a resin-modified glass-ionomer with calcium on enamel demineralization inhibition: an in vitro study[J]. Braz Oral Res, 2019, 33: e015. DOI:10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2019.vol33.0015 |

| [78] |

De Moor RJ, Stassen IG, van't Veldt Y, et al. Two-year clinical performance of glass ionomer and resin composite restorations in xerostomic head- and neck-irradiated cancer patients[J]. Clin Oral Investig, 2011, 15(1): 31-38. DOI:10.1007/s00784-009-0355-4 |

2023, Vol. 43

2023, Vol. 43