随着细胞组学研究的不断进展,采用胞质分裂阻滞(cytokinesis-block,CB)方法可通过分析核质桥(nucleoplasmic bridge,NPB)、微核(micronucleus,MN)检测染色体损伤程度,已成为检测染色体断裂或丢失、染色体不分离、DNA错误修复、细胞坏死或细胞凋亡的综合方法[1]。淋巴细胞核质桥具有较好的剂量-效应关系[2-3],具有应用自动化技术进行分析的前景[4],有可能应用于辐射生物剂量估算等领域[5]。

传统的胞质分裂阻滞实验方案中,需要进行72 h的细胞培养,且要在细胞培养过程中加入松胞素B(cytochalasin-B,Cyt-B)[6]。在核和辐射事故发生后,时间是抢救生命的关键,快速、准确的估算人员受照剂量是医学应急的重要任务之一[7]。如能缩短细胞培养时间并简化实验步骤,有可能更快地得到生物剂量估算结果,对受照人员的临床救治具有重要意义。本研究通过分析细胞培养时间及培养开始加入松胞素B对辐射诱导核质桥水平的影响,旨在探索缩短胞质分裂阻滞方法细胞培养时间和简化实验步骤的可行性,为以核质桥为指标进行生物剂量估算提供依据。

材料与方法1.样本采集:在知情同意条件下,抽取26岁健康男性外周血8 ml,注入肝素抗凝管。本研究通过中国疾病预防控制中心辐射防护与核安全医学所伦理委员会审查。

2.样本照射:在北京辐照中心用2 Gy 60Co γ射线对离体外周血进行照射,剂量率为1 Gy/min。照射源放射性活度为130 TBq,均匀照射野为30 cm×30 cm。本研究设0 Gy对照,不接受射线照射,其余条件与照射组相同。

3.细胞培养:外周血样本在37℃温箱中修复2 h后,吸取400 μl加入至2.0 ml含20%胎牛血清的RPMI 1640培养基(美国GIBCO公司)、0.2%植物凝血素(phytohemagglutinin,PHA)(美国Sigma公司)及青链霉素(美国GIBCO公司)。每个样本设2个平行样。

(1) 为探索不同细胞培养时间对核质桥水平的影响,根据不同培养时间分为48、56、68和72 h组。细胞在培养28 h后,加入终浓度为6 μg/ml的松胞素B(美国Sigma公司),混匀后继续避光培养,分别在培养48、56、68和72 h收获。

(2) 为探索培养开始加入松胞素B对核质桥水平的影响,根据不同松胞素B终浓度分为0.6、1、2、6和10 μg/ml组。在培养开始时(0 h),分别加入终浓度为0.6、1、2、6、10 μg/ml的松胞素B,混匀后继续避光培养至68 h收获。

4.细胞收获:将样本1 000 r/min,离心半径10 cm离心10 min,吸去上清,加入氯化钾(KCl)低渗液(0.075 mol/L),室温低渗1 min。用固定液(甲醇∶冰乙酸=3 ∶1,v/v)固定2次后得到细胞悬液。取100 μl悬液在干玻片上滴片,用吉姆萨染液染色,冲洗晾干,将所有标本随机编号。

5. 阅片分析:光学显微镜下(×400倍或×1 000倍)每个样本分析1 000个转化细胞,记录单核、双核及多核细胞数量。每个样本分析1 000个双核细胞(若不足1 000个,按实际分析细胞数计数),记录核质桥及微核数量。判定标准参照国际原子能机构(IAEA)提出的标准[8]。

6. 统计学处理:核分裂指数(nuclear division index,NDI)=(M1+2×M2+3×M3+4×M4)/N;双核细胞比例=M2/N×100%,双核及多核细胞比例=(M2+M3+M4)/N×100%。其中M1~M4分别为单核、双核、三核及四核细胞数量;N为分析的转化细胞数量。采用SPSS 26.0软件进行统计学分析,核质桥率、微核率、核分裂指数比较采用Mann-Whitney U检验,双核细胞比例、双核及多核细胞比例比较采用χ2检验。P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

结果1. 不同细胞培养时间对核质桥及微核的影响:细胞在培养28 h后加入终浓度为6 μg/ml的松胞素B,继续培养至48~72 h收获。各组核分裂指数、双核细胞比例见表 1。0 Gy组中,核分裂指数、双核细胞比例均随细胞培养时间的增加而升高,且与72 h组相比,差异均具有统计学意义(U=2.72~8.67、χ2=25.51~121.23,P < 0.01)。2 Gy组中,核分裂指数及48、56、68 h 3组的双核细胞比例随细胞培养时间的增加而升高,48、56 h组与72h组相比,差异均有统计学意义(U=6.41、8.54,χ2=7.22、47.97,P < 0.01)。2Gy各收获时间点的核分裂指数、双核细胞比例、双核及多核细胞比例均高于0 Gy(U=4.24,χ2=12.34~65.13,P < 0.01)。

|

|

表 1 不同细胞培养时间组的核分裂指数及双核细胞比例 Table 1 The nuclear division index and the proportion of binucleated cells at different cell culture times |

照射后不同培养时间的核质桥率及微核率见表 2、图 1。各组分析1 000个双核细胞,核质桥率随细胞培养时间的增加有降低的趋势(0.0330~0.0230/细胞),但差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。微核率随细胞培养时间无明显规律(在0.3850~0.4670/细胞),差异亦无统计学意义(P > 0.05)。

|

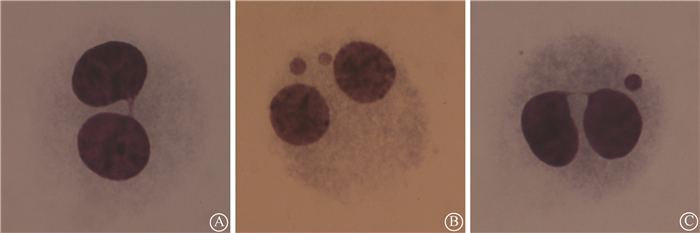

图 1 2 Gy 60Co γ射线诱导的双核细胞中的核质桥和微核 A. 双核细胞中的1个核质桥;B.双核细胞中的2个微核;C.双核细胞中的1个核质桥和1个微核 Figure 1 2 Gy 60Co γ-ray induced nucleoplasmic bridge and micronucleus in binucleated cells A. One binucleated cell with one nucleoplasmic bridge; B. One binucleated cell with two micronuclei; C. One binucleated cell with one nucleoplasmic bridge and one micronucleus |

|

|

表 2 2 Gy 60Co γ射线照射后不同细胞培养时间组的核质桥率及微核率(p±sp) Table 2 2 Gy 60Co γ-ray induced nucleoplasmic bridges and micronuclei frequencies at different cell culture times after irradiation(p±sp) |

2. 培养开始加入松胞素B对核质桥及微核的影响:培养开始加入终浓度为0.6~10 μg/ml的松胞素B,培养68 h收获。各组核分裂指数及双核细胞比例见表 3。0 Gy核分裂指数、双核细胞比例有随松胞素B浓度增加而升高的趋势,与6 μg/ml组相比,差异均有统计学意义(U=2.72~5.04,χ2=41.72~128.29,P < 0.01)。2 Gy双核细胞比例具有随松胞素B浓度增加而升高的趋势,与6 μg/ml组相比,差异均有统计学意义(χ2=7.09~28.64,P < 0.01)。2 Gy的0.6、1、2、6 μg/ml 4组的核分裂指数、双核细胞比例、双核及多核细胞比例均高于相同浓度的0 Gy组。

|

|

表 3 不同松胞素B终浓度组的核分裂指数及双核细胞比例 Table 3 Nuclear division index and proportion of binucleated cells in the culture treated with different concentrations of cytochalasin-B |

培养开始加入不同浓度松胞素B的核质桥率及微核率见表 4。2 Gy组中,不同浓度组分析了234~372个双核细胞,核质桥率随松胞素B浓度增加无明显变化规律,在0.023 0~0.047 0/细胞之间,差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05)。微核率随松胞素B浓度增加无明显变化规律,与6 μg/ml组相比,10 μg/ml组显著降低(U=2.74,P < 0.01)。0 Gy不同浓度组分析了101~497个双核细胞,未观察到核质桥,观察到0~4个微核,差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05)。

|

|

表 4 不同松胞素B终浓度组核质桥率及微核率(p±sp) Table 4 Nucleoplasmic bridges and micronuclei frequencies in the culture treated with different concentrations of cytochalasin-B(p±sp) |

讨论

核质桥是胞质分裂阻滞分析的重要研究指标,是DNA错误修复、染色体重排和端粒末端融合的生物标志物[6]。染色体畸变分析是目前电离辐射生物剂量估算的“金标准”,核质桥源于双着丝粒染色体[9];核质桥容易分析鉴别,并有可能实现自动化分析[4, 10]。本实验室前期研究已证实核质桥在较高剂量范围(0~6 Gy)[2]及较低剂量范围内(0~1.0 Gy及0~0.4 Gy)[11],均具有良好的剂量-效应关系;且核质桥本底水平较低[12],这些是核质桥成为辐射生物剂量计的基础条件。

细胞经过不同培养时间后,辐射诱导核质桥率差异并无统计学意义,微核率无明显变化规律,因此对以核质桥或微核为指标进行生物剂量估算的准确性影响较小。双核细胞比例具有随细胞培养时间缩短而降低的趋势,当细胞培养时间缩短至48 h,双核细胞比例为34.6%,低于传统方法(培养72 h),会对人工分析效率造成一定影响,但仍比传统方法得到核质桥分析结果的时间提前20 h以上[6]。在应急情况下进行生物剂量估算时,越快得到生物剂量信息,越有利于受照人员的临床救治。且随着自动化分析技术的不断进展,从得到核质桥标本到估算生物剂量的时间会大幅缩短,尤其是在进行大人群的生物剂量估算中。因此,可适当缩短细胞培养时间,提前获得核质桥分析结果,进而进行生物剂量估算。

本实验室前期研究发现了双核细胞比例随松胞素B浓度的增加而上升[13]。研究表明,在进行染色体标本制备时,培养开始和培养过程中加入秋水仙素的浓度不同[14]。本研究在培养开始加入不同浓度的松胞素B,发现双核细胞比例同样具有随松胞素B浓度的增加而升高的趋势,但双核细胞比例最高的10 μg/ml组为31.6%,低于在培养过程中(28~44 h)加入松胞素B的双核细胞比例[13],可能会影响分析效率。此外,培养开始加入松胞素B后,可供分析的双核细胞数较少。仅分析了0 Gy 101~497个双核细胞,2 Gy组仅分析了234~372个双核细胞,辐射诱导核质桥率差异无统计学意义,而10 μg/ml组微核率显著降低,可能是由于松胞素B的细胞毒性作用造成。因此,在培养开始加入松胞素B虽可简化在培养过程中的实验操作步骤,但导致可供分析的双核细胞数量较少,很难满足剂量估算的要求。

综上所述,本研究用2 Gy 60Co γ射线照射人离体外周血,用胞质分裂阻滞法进行标本制备,48~72 h范围内不同细胞培养时间对辐射诱导核质桥率及微核率差异无统计学意义。培养开始加入不同终浓度松胞素B导致可供分析的细胞数量较少,对辐射诱导核质桥率差异无统计学意义,但对微核率具有一定影响。总之,适当缩短细胞培养时间可提前得到核质桥分析结果,对应急情况下生物剂量估算具有重要意义;培养开始加入松胞素B可简化实验步骤,但导致可供分析的细胞数过少,用于剂量估算的可行性尚需进一步研究。

利益冲突 无

作者贡献声明 赵骅负责实验操作、数据分析、论文撰写;蔡恬静、陆雪协助实验操作、数据分析;田梅、刘青杰指导课题设计和论文修改

| [1] |

Fenech M. Cytokinesis-block micronucleus assay evolves into a "cytome" assay of chromosomal instability, mitotic dysfunction and cell death[J]. Mutat Res, 2006, 600(1-2): 58-66. DOI:10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.05.028 |

| [2] |

Zhao H, Lu X, Li S, et al. Characteristics of nucleoplasmic bridges induced by 60Co γ-rays in human peripheral blood lymphocytes[J]. Mutagenesis, 2014, 29(1): 49-51. DOI:10.1093/mutage/get062 |

| [3] |

Cheong HS, Seth I, Joiner MC, et al. Relationships among micronuclei, nucleoplasmic bridges and nuclear buds within individual cells in the cytokinesis-block micronucleus assay[J]. Mutagenesis, 2013, 28(4): 433-440. DOI:10.1093/mutage/get020 |

| [4] |

Rodrigues MA, Beaton-Green LA, Wilkins RC, et al. The potential for complete automated scoring of the cytokinesis block micronucleus cytome assay using imaging flow cytometry[J]. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen, 2018, 836(Pt A): 53-64. DOI:10.1016/j.mrgentox.2018.05.003 |

| [5] |

Nairy RK, Bhat NN, Sanjeev G, et al. Dose-response study using micronucleus cytome assay: a tool for biodosimetry application[J]. Radiat Prot Dosim, 2017, 174(1): 79-87. DOI:10.1093/rpd/ncw045 |

| [6] |

Fenech M. Cytokinesis-block micronucleus cytome assay[J]. Nat Protoc, 2007, 2(5): 1084-1104. DOI:10.1038/nprot.2007.77 |

| [7] |

Sproull M, Camphausen K. State-of-the-art advances in radiation biodosimetry for mass casualty events involving radiation exposure[J]. Radiat Res, 2016, 186(5): 423-435. DOI:10.1667/RR14452.1 |

| [8] |

International Atomic Energy Agency. Cytogenetic dosimetry: application in preparedness for and response to radiation emergencies[R]. Vienna: IAEA, 2011.

|

| [9] |

Kravtsov VY, Livanova AA, Belyakov OV, et al. The frequency of lymphocytes containing dumbbell-shaped nuclei depends on ionizing radiation dose and correlates with appearance of chromosomal aberrations[J]. Genome Integr, 2018, 9(1): 1. DOI:10.4103/genint.genint_1_18 |

| [10] |

Zaguia N, Laplagne E, Colicchio B, et al. A new tool for genotoxic risk assessment: reevaluation of the cytokinesis-block micronucleus assay using semi-automated scoring following telomere and centromere staining[J]. Mutat Res, 2020, 850-851: 503143. DOI:10.1016/j.mrgentox.2020.503143 |

| [11] |

Tian XL, Zhao H, Cai TJ, et al. Dose-effect relationships of nucleoplasmic bridges and complex nuclear anomalies in human peripheral lymphocytes exposed to 60Co γ-rays at a relatively low dose[J]. Mutagenesis, 2016, 31(4): 425-431. DOI:10.1093/mutage/gew001 |

| [12] |

Shimura N, Kojima S. The lowest radiation dose having molecular changes in the living body[J]. Dose Response, 2018, 16(2): 1559325818777326. DOI:10.1177/1559325818777326 |

| [13] |

赵骅, 陆雪, 田雪蕾, 等. 松胞素B对辐射诱导淋巴细胞核质桥水平影响的研究[J]. 中华放射医学与防护杂志, 2017, 37(8): 576-580. Zhao H, Lu X, Tian XL, et al. Influences of cytochalasin-B on radiation-induced nucleoplasmic bridges in peripheral blood lymphocytes[J]. Chin J Radiol Med Prot, 2017, 37(8): 576-580. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-5098.2017.08.003 |

| [14] |

Chen DQ, Zhang CY. A simple and convenient method for gaining pure populations of lymphocytes at the first mitotic division in vitro[J]. Mutat Res, 1992, 282(3): 227-229. DOI:10.1016/0165-7992(92)90100-v |

2021, Vol. 41

2021, Vol. 41